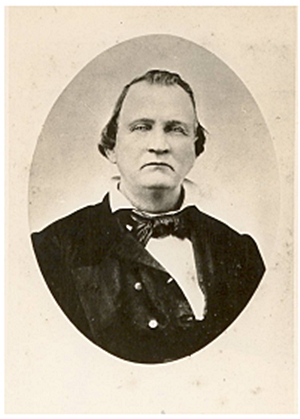

George Washington Wright by: Skipper Steely About 5’-10,” 225 pounds, and blue-eyed with black hair as a young adult, George Washington Wright was born east of Carthage, Tennessee on December 11, 1809. He became the most politically active of Claiborne and Elizabeth Travis Wright’s five children. He also farmed, dealt with real estate and had a mercantile career for most of his life.

For only seven years Wright could call a place on the Cumberland River home. In March of 1816 his father, mother and three servants packed up belongings onto a keelboat and began a six months trip to the far frontier of property thought to be owned by the United States. Just why they moved to west of the Great Bend of the Red River of the South is unknown but the six months tour down the busy Cumberland, the scenic Ohio and wide Mississippi Rivers and then up the Red River was an adventure Wright would describe in detail often during his lifetime.

Wright’s young adulthood was spent learning how to survive in the wilds, whether it was hunting buffalo on the prairies west of what is now Paris, Texas or near Madil, Oklahoma, or hiding from the feared Osage Indians who came through the Red River Valley now and then to hunt. His father was a member of the Territory of Arkansas Legislative Council and sheriff of what was Miller County, now Northeast Texas and Southeast Oklahoma. The first Wright home was at Pecan Point, on the south side of the Red River in territory Spain also claimed. Later, the Wright home would be the county court and was next to the Clear Creek tributary north of the Red River near present Valliant, Oklahoma.

Many neighbors came and went, especially when it was announced in 1820 that the northern portion of Miller County had been treatied to the Choctaw Indians. Many friends and neighbors left to move south to East Texas or to join Stephen F. Austin’s colonization effort. Therefore, as Wright grew into manhood and took an active part in business and politics, his association with so many who moved south would later assist him when he represented Northeast Texas in the Republic of Texas Congress.

However, the 1820’s were not stable for the settlers, who never gained title to lands they inhabited. A strong link continued between those living west in Miller County and those in the large mother county called Hempstead. The main highway into Texas came through Arkansas, basically what is U.S. Highway 67 today. Letters back home from these far southwestern settlements brought a flood of settlers both down the road and up Red River. Even though the Americans were moved south of Red River to make room for Indian tribes coming over from east of the Mississippi, the temptation to own large chunks of land intrigued many Americans who came from the former territories of Illinois, Indiana and Missouri. They hoped to eventually have a homestead in the southwest similar to those gained in the Northwest Territories many years before.

On February 13, 1834 George Wright married Matilda Holman of Hempstead County, Territory of Arkansas. She was the daughter of James Holman and granddaughter of John Holman, a Revolutionary War soldier who lived near Columbus, Arkansas. The Wrights did not choose to live in the vicinity of the Holman farm but moved to land owned by Wright at the far western edge of settlements in Miller County, Territory of Arkansas. He had purchased it in 1831.

The farm or small plantation banked upon the Red River, across from the mouth of the clear and pure waters of the Kiamichi River. Thus the place was called the Kiomatia Plantation or Wright Farm.

For the next five years Wright farmed the acreage as part of Miller County but soon it became apparent that the United States would never allow the settlers land claims to their properties. Neither could an agreement be struck with Mexico. Thus, Red River Valley inhabitants turned their interest south toward the efforts of Anglo-Texans. Many were friends who once lived near the shifting sands of the Red River.

Continuous Indian threats from the west kept the Red River settlements from contributing many men to help when war with Mexico seemed inevitable. Finally, the Red River settlements made their choice by sending delegates to the Independence Convention in March, 1836.

In the early spring of 1836 the Red River settlements received a message from David Burnet to assist the Texian cause. Wright eventually responded, first taking his wife Matilda and their two daughters Nancy Jane and Elinor to the Holman farm in Hempstead County.10 Wright then, by family lore, rode south to assist the Texas cause against the Mexicans. If Wright was at or near the San Jacinto Battleground in April of 1836 there is no evidence available. It is known that on July 6 of that year he joined with Captain John Hart’s command at Jonesboro and went to Dimmitt’s Landing area of south Texas to help guard the frontier from a second Mexican invasion.

While there he was elected on September 5 to serve as one of the three Red River District representatives in the first Republic of Texas Congress to be held at Columbia. On the next to last day of the session he filed an expense voucher dated December 21, 1836, saying he was entitled to $660 for 52 days travel and 80 days attendance. The 80 days is correct but where he got the travel time is unclear. Perhaps Wright included several days of travel while serving. His discharge from military service is different than others in his command. Instead of being October 14, his says December 12. For his service with Hart he received a 320 acre grant in Hunt County.

The upbeat weeks that were spent in an active role creating a new country soon changed to personal sadness for Wright. When he returned to the Columbus, Arkansas area to celebrate a late Christmas with his family he found out the two young daughters had sickened and died. He and Matilda returned to Kiomatia childless.

Shortly after the independence of Texas the Red River District land commissioners met in Wright’s home on a mound facing a bend in the Red River. It became one of the eleven such offices established in Texas to register land claims. For the first time Red River Valley residents would be able to officially claim their land.

Before he was elected as representative to the Third Texas Congress in the fall of 1838 Wright had two children again: William “Joggles” Travis and Emily Brown Wright. At the Houston Congressional gathering Wright was joined also by his first cousin John Hopkins Fowler and Isaac Newton Jones. Richard Ellis of the Red River District was again elected the area’s senator. The meeting lasted until January 24, 1839.

Because he kept having re-occurring bouts with malaria, Wright left his farm of 3,432 acres across from the Indian Territory in 1839, selling it to his brother Travis Wright and including another tract of 100 acres in Lamar County with a tenant house on it, and six slaves. Having been successful at farming, thanks to corn contracts originally with the governmental move of the Choctaw Indians, George Wright then purchased 1,000 acres for $2,500 from Illinoian Larkin Rattan. The land was in western Red River County, on a hill in the middle of what would become Lamar County in late 1840. It was located just a half-mile from the Claiborne Chisum/Johnny Johnson settlement which was on a sharp turn in the road called Pinhook.

The land Wright purchased was on a crest that separated the watershed between the Red River about 15 miles to the north and the Sulphur River the same distance to the south. He constructed a rather large home at what is now 304 Third SW in Paris. Wright opened up a business about one-quarter mile to the northeast on the hill.

In 1840 Wright is listed on the tax roles as owning 3,600 acres, 21 slaves, 15 cattle and 10 horses. This was probably filed before he sold the Kiomatia farm. He moved the family to the new home in mid to late 1840 and in December of that year a new county was formed around his property. On February 1, 1841 Lamar County’s first court was held at the Wright home. Wright was chosen as the county’s first coroner. He was also elected as a justice of the peace for Beat #7 on March 20.

Though he is not listed on any muster roles of groups that went on Indian expeditions from 1837 - 1843, there is evidence he, like his brother Travis, provided goods for the groups. For instance, he bound himself to deliver 8,000 pounds of “good mercantile bacon,” a portion to be delivered to Fort Johnson on or before March 15, 1841. This would be shortly before a large contingent gathered there to march with E. H. Tarrant on the Indians camped at the Three Forks of the Trinity River.

During the first months of the Lamar County court activities Wright signed a surety to the bonds of several office holders. He worked closely with his first cousin Alexander Jackson Fowler, who was an early judge. Wright even drew the first fine administered from the county court--for contempt when he apparently protested out of order. Not taking this personally, the commissioners then planned the new Lafayette court house to be along the plan of the Wright home.

After two sites proved unsuitable for a Lamar County seat Wright offered 50 acres out of his property for a new city. His store would be in the northwest corner. Thus, on April 29, 1844 Lamar county first used the site called Paris as its meeting point. The city was surveyed by George W. Stell, incorporated the next year and the final deed transaction was presented to the court in 1848.

For over a decade Wright’s home continued to be on what is now First SW, partially used as a hotel. Out of the 50 donated acres he kept three lots, each sized 54’ x 108. One was his store site on the north end of the west side of the square, one on the east side of the square on the north end, and one about the center of that side.

For many years in the 1940-1960 period of time the site of the original survey call for the city of Paris was notated on the side of a building at the corner of West Price and Third NW. However, after the First National Bank cleared the block in the early 1960s a marker was placed on the that corner on March 11, 1966, donated by oilman Michael T. Halbouty of Houston, principal owner of the bank at that time.

In the fall of 1844 Wright prepared to travel to Washington-On-The-Brazos to serve as a senator of the Ninth Republic of Texas Congress representing Lamar, Red River, Fannin and Bowie Counties. However, illness prevented his participation in the early portion of its activities. The regular session lasted from December 2, 1844 to February 3, 1845. Two days before its conclusion Wright moved to take up William H. Bourland’s January 23 bill to incorporate Paris. It was passed February 1, covering 160 acres of territory. He did attend a Washington-On-The-Brazos called session held from June 16, 1845 - June 28, 1845. Subsequently, he also served from July 4 - August 28, 1845 as a member of the Constitutional Convention in Austin, helping construct the first document for Texas as a state of the Union.

By 1846 commerce was arriving in the area regularly and Wright advertised his Lamar Hotel as newly arranged for travelers and their teams. It had good beds and plenty of feed and a stable room with careful hostlers. It was an addition to his two story, double log house on what was called South Mill Street [3rd SW]. Competition was being built, however, on the square by Johnny Johnson. It was called the Paris Inn.

The Wrights and the hotel took a big setback when Matilda died on October 4, 1848, about three weeks after the birth of the couple’s sixth child, Mary Eliza. Matilda never regained her strength from the hard labor. The now four living children were left to the care of family servants and friends.

In 1850 Wright listed his worth at $28,010. On March 13 of that year, at 39 he married 28 year old Sarah Jane Mebane, also a native of Tennessee. She was the daughter of Robert Mebane.39 The Reverend Samuel Corley, performed the ceremony. Ironically, he was Presbyterian, not Methodist as was Wright. This union between the Wright and Mebane family did not last long. Sarah Jane Wright died apparently during or after childbirth on May 18, 1853. The child died, also.

For the first time Wright ventured into national politics, jumping into the Eastern Congressional District race for the United States House of Representatives. However, the competition was fierce. William R. Scurry took the seat to the 32nd Congress but in Lamar County Wright came in second August 4, 1851 and ahead of William Beck Ochiltree, a colleague of Wright at the Annexation Convention and Fifth Judicial District judge. Scurry really had the advantage since he had lived in Clarksville at one time, and at the time of the election was a citizen of San Augustine County in deep East Texas.

Wright continued active in the new Paris community. In 1852 the town petitioned the legislature to incorporate it again at 640 acres. In 1853 he became involved in the dream to construct a railroad across Texas toward the Pacific Ocean. He became an officer and investor in the Memphis, El Paso and Pacific Railroad venture. This nationally chartered effort would be time consuming the next seven years as would a venture into the newspaper business! He and others financed W. J. Foster’s Frontier Patriot in 1856. It lasted only two years. Paris never had a shortage of newspaper operations in the 19th century.

For some reason Wright moved the family to the countryside four miles south of Paris in early 1855, probably locating on the south side of the Sarah Cross Headright. He sold the old town home to George Bonner for $950, mostly to be paid in notes. The place south of town on the Cross Headright was called “Woodland” by Will Williams who lived nearby. Wright had owned the land since 1849, gaining title when real estate investor Joshua Bowerman died, owing a note of $7,197.43 to Wright. The house there was a one-story, board lumber structure some 65 feet in width with a wide pillared porch across the front.

In January of 1858 George Wright’s oldest daughter, Emily, married James Mitchell Daniel, the railroad expert Wright helped hire in 1856 as principal engineer of the MEPPRR project. Two years later Wright himself married for a third time. The ceremony to Sara Ann Wingo was performed by Methodist preacher James Graham in 1858. Wright had supported the Methodist Church in Paris from its inception in 1843. When the 1860 marriage was performed the church was on the northwest side of the city. A small cemetery was started to the east of the building, now called the Old City Cemetery, once named the Wright Cemetery. Many pioneers of Paris are buried there, however, including Wright and his three wives.

When the fall of 1860 arrived meetings were being held periodically to discuss the pros and cons of secession from the United States. The election of Abraham Lincoln alarmed many. When a Texas convention was finally called in January of 1861 to allow a statewide discussion on the matter, Wright, Lem Williams and William H. Johnson were selected to attend from Lamar County. Wright was an old-line Whig and Unionist. All three voted against secession, following the lead of Governor Sam Houston, a man Wright originally met back in 1834. Only five others cast a negative vote with Lamar Countians. At the time Wright owned 35 slaves and was worth $75,000. Still, he saw no sense in a withdrawal from a union he and so many others had fought hard to join just 15 years prior.

When the vote was taken the citizens of the county were mostly in concurrence with their delegates. Lamar County was one of only 19 counties in Texas voting to stay in the Union. However, when secession came, Wright and the other two delegates joined in the Confederate cause. Wright was appointed provost marshal for the county. He obtained arms, ammunition and powder from New Orleans for Confederate units being formed in Lamar County. His son, James Holman [Jim] Wright, served with Travis Wright’s son Sam as members of Captain Daniel’s Artillery Battery, later to be known as the 9th Texas Field Artillery.

Wright’s elder son “Joggles,” or Bill, left for the west in late 1859 and at one time was presumed dead. He was not and returned home for a brief visit in 1866 before heading back to his home in Virginia City, Nevada. Jim Wright and Captain Daniel both survived the Civil War to return to Paris. However, the war severely damaged the railroad dream although Daniel pursued it for several years.

In the fall of 1866 it was clear the Old City [Wright] Cemetery was too penned in to expand to meet the needs of the city. Wright and ten men formed the Evergreen Cemetery Association. Wright sold it 16 acres and later the association purchased more land from P. P. Cook and Sam Bell Maxey. Some relatives moved the remains of loved ones from the old cemetery to Evergreen. Five of Wright’s children are buried at Evergreen.

In 1868 Wright moved his family, now consisting of the two young daughters at home, to the George Bason Headright southwest of Paris about three miles. He supposedly gave “Woodland” to his daughter Mary Eliza when she married William H. Jennings in 1869. Wright had purchased the 714 acres of the Bason Headright from his sister, Henrietta. Bason was her second husband. The land was not patented until 1858. The Wright home there became known simply as the “Old Wright Homestead.” The house was to the east of Aud’s Creek [once called Crockett’s Creek in honor of when that pioneer crossed northeast Texas], in the northern portion of the land. Not too far away, toward town, was the new fair grounds site. Wright was a director when the first session of the Lamar County Agricultural and Mechanical Association was held there in 1868.

The stay there was short, for in the summer of 1871 the house burned. Wright then purchased two and four-fifths acres of land on a hill in the Asa Jarman Survey, not too far southwest of his original Paris home. The address is now 801 West Sherman. Here he constructed a two-story, wooden house shaped in the familiar L with appropriate outhouses. It apparently had a 12 deep layer of brick, four wide, as a foundation. Not only did his wife and two daughters live there, but his brother-in-law Ezra Wingo who had been living with the Wrights since 1860.

In 1871, a few months after Paris received yet another state charter to expand to a league and a labor [4,428 acres + 177 acres], Wright began posing for a painting being developed by a young artist named William Henry Huddle. Wright consented to be Huddle’s first commissioned work in Texas, but many Parisians, including Williams and Johnson, posed for Huddle portraits.

Probably while the painting was in progress Wright was investing in another railroad venture--a line to be from Paris to Bonham to connect to the Katy coming to the Red River from the north. It never materialized. When the work was finished on the portrait, Huddle handed a cane to Wright. On it were carved the many events that Wright had seen in his Texas lifetime. The Wright painting now hangs in the Texas Capitol Library. In fact, the Capitol has 32 Huddle paintings, including his most famous work, The Surrender Of Santa Anna, viewed by all who enter through the south door. Not entirely through with politics, Wright was appointed by Governor Richard Coke to attend the National Democratic Convention at St. Louis in 1876. That was his last public act. On August 2, 1877 Wright succumbed to a hemorrhage of the stomach, two weeks after he moved into a new home. He had lived under six flags during his lifetime--Territory of Arkansas, Spain, Mexico, Texas, United States and the Confederate States of America. He was buried in the Old City Cemetery within his Larkin Rattan headright. A few years later a large stone was erected there, with inscriptions for Wright and his three wives. This article appears on the Texas History Page by permission of Skipper Steely all rights reserved |